Taryn Tavener-Smith is a full-time Lecturer at Buckinghamshire New University. She is in the fourth year of a part-time practice-based PhD in English Studies with the University of Stirling. Taryn’s research explores the portrayal of liminal identities in non-fiction life writing.

Finding the time and space to write as a part-time doctoral researcher can feel like an immense challenge, especially when this needs to fit alongside a full-time academic role. In this blog, I will share what I have learned about establishing my own writing practice.

I started my part-time practice-based PhD in English Studies in September 2020 while working full-time. Following enrolment, I encountered the seemingly insurmountable task of churning out a 70,000-word creative artefact alongside a 30,000-word critical piece detailing my reflections on the writing process. Once the initial panicked flailing of the project’s breadth had subsided, I started writing: I wrote in brief bursts for an hour before work each morning; I wrote for brief 15-minute intervals throughout the working day between lectures, seminars, student and faculty meetings (such writing spells were less frequent); I wrote in the evenings for momentary bursts when my otherwise weary brain permitted (these occurrences were even scarcer).

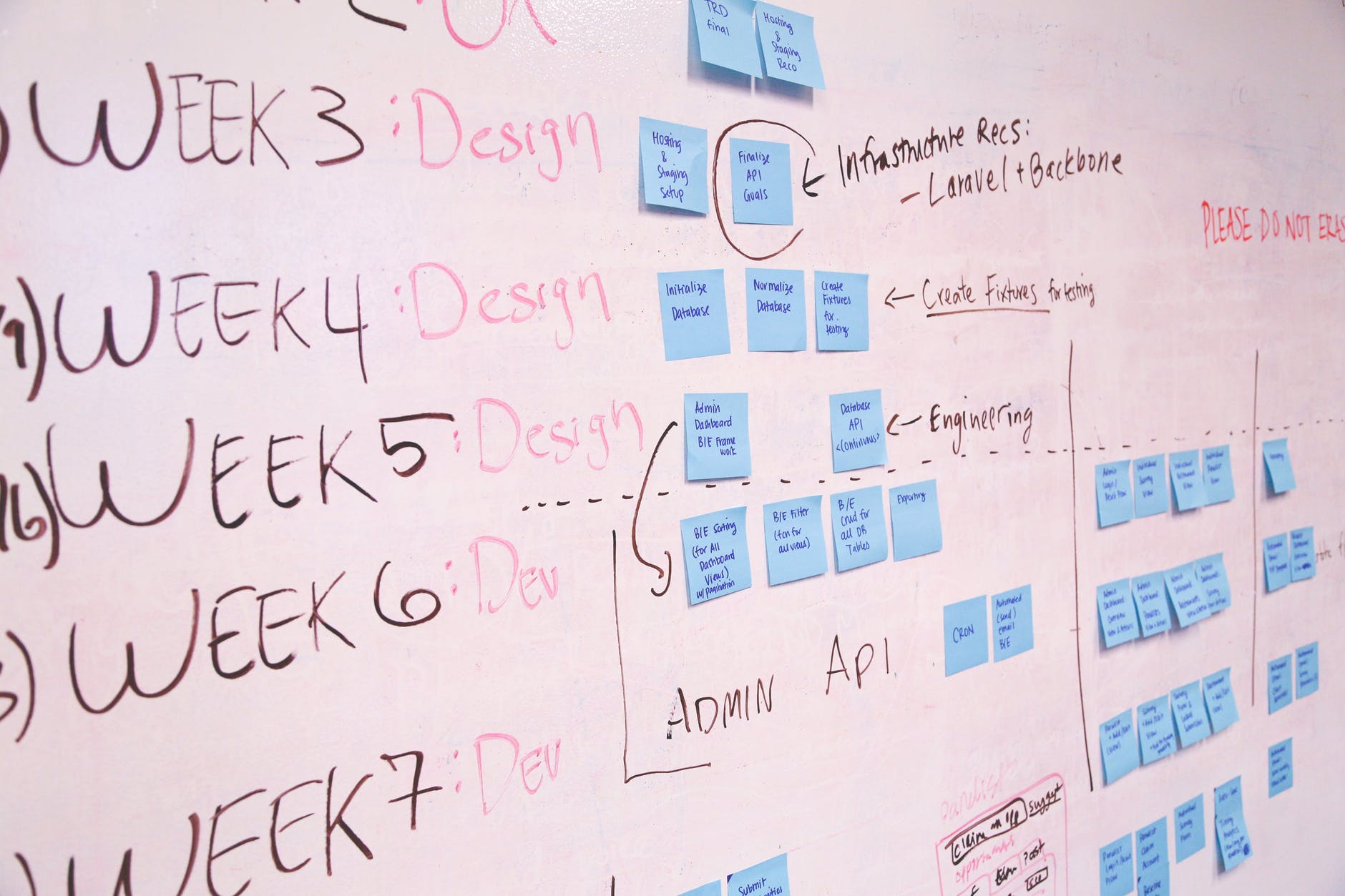

These non-sequential writing hours eventually clocked into writing days and, later, into entire weeks that morphed into blurry months. My writing practice (if I can even call it that) was punctuated by endless reams of fragmented text. Before long, the project’s content began swirling around my desk in several forms: crumpled Post-it notes, haphazardly constructed reminders in my mobile’s Notes, hastily typed, misspelt emails to myself, and scribbled musings on jagged-edged pieces of paper.

Suddenly though, something miraculous happened: I had a page completed. Then two. Then three. Then twenty pages. Before I knew it, an entire chapter had been written. But this was not a supernatural occurrence – all it boiled down to was gradually establishing a writing practice (more or less) and sticking to it (well, mostly sticking to it). Not everything I wrote was any good, either. In fact, much of the material produced during those earlier days has since been relegated to the proverbial ‘cutting room floor’, while William Faulkner’s reminder to ‘Kill your darlings!’ echoed in my ears.

Here are some things I have learned about writing during the first four years of part-time PhD study:

- Find your ‘tribe’ and attend writing retreats: Your ‘tribe’ can be anyone: a local writing group; a collection of students or scholars who are interested in writing; novice writers practising the craft for enjoyment. These communities reinforce accountability while making the (often isolating) PhD journey feel less lonely. These groups are also well established to support writers from all disciplines, interests, and walks of life. If you cannot locate any local writing groups, establish your own by reaching out to peers at your institution.

- Write less, more often. An advisor once gave me a piece of advice about dissertation writing: ‘Just start by writing a room in the house and forget about writing the entire house!’ This caveat has remained with me. It reminds me of the significance that even the most rudimentary of initial steps often holds in terms of writing practice.

- Write anything! We often possess the misconception about obtaining ‘perfection’ in our writing from the outset. We hold ourselves to standards that are not only unattainable (in the first draft, anyway) but that are often stifling to our progress. We assume that unless a piece of text is ‘perfect’, it fails to convey progress. First drafts will never be perfect and are called ‘drafts’ for exactly that reason, but they are still undeniably valuable components on the journey toward perfection (if such a thing even exists). And, if this fails, remember the well-used ‘cutting room floor’ idea from earlier.

- When it comes to writing practice – you need to do just that: practice. Writing is a craft requiring practice. We take pride in practising various other skills in our daily lives and writing is no different. It requires practice if it is to be mastered.

Four years on, I have reached the conclusion that the PhD endeavour (regardless of discipline) is firmly rooted within writing practice and as such, calls for clear acknowledgement of this fact. The importance of identifying suitable approaches to writing, establishing a writing practice, and actually executing that practice consistently (regardless of how fragmented it may appear in the moment), cannot be overstated. Writing in a PhD is ultimately a journey, whose destination can only be reached in one way: by writing. One. Word. At. A. Time.